Alex Gillis Takes on a “Killing Art.”

Alex Gillis. A Killing Art: The Untold History of Tae Kwon Do. Ontario: ECW Press. 2011 (First published in 2008). 246 pages. $16.95 USD.

As I mentioned here I am assembling a reading list for an undergraduate course on the Asian martial arts. My preference would be to teach it in a political science department and use the martial arts to explore topics like identity, nationalism, imperialism and globalization. However, at the moment I am actually in talks with an anthropology department who would probably prefer more emphasis on culture, society and Asian studies.

One way or another, it is time to build my reading list. I am planning on looking at case studies in China, Japan, Korea and the US. Hopefully students will find a broad comparative landscape to be helpful. Most of my expertise centers around the Chinese arts. I know enough about Japan to scrape together a plausible reading list, but Korea?

Korea is a problem. Why? Imagine standing at the front of a class at any large state university. Most of the people in your class are going to be there because they are either martial artists themselves or are interested in the entertainment sub-culture that they have given rise to. You want the students to be able to identify with the readings and the discussion on a personal level because that will lead them to be more engaged. If you go around the room which martial art do you think that most of your students will have been exposed to in the past?

Tae Kwon Do. The answer is always Tae Kwon Do. Soccer moms with hyperactive eight year olds enroll their children in Tae Kwon Do classes, not Silat seminars or Wing Chun schools. What this means for you as a teacher is that you are likely to have a lot of undergraduates whose main exposure to the martial arts will have been a couple of years of Tae Kwon Do training in middle school.

Revealing the Hidden History of Tae Kwon Do

A Killing Art, by Alex Gillis, is sure to appeal to these students. Actually, the book is fantastic. It is a must read for anyone who is interested in the modern history of the Asian martial arts. The writing is clean and it flows easily, reflecting the author’s background in journalism. The book presents a well-researched study of the history of Tae Kwon Do. It begins with the style’s origins among a group of Korean youth who studied Japanese Karate before WWII and concludes with the present day controversies surrounding the sport’s continued inclusion in the Olympics.

Gillis’ background as an investigative reporter is much in evidence throughout this study. The number of interviews that he managed to conduct was truly prodigious, and many of the topics that he had to convince individuals to “go on the record” about (corruption, kidnapping, torture) were, quite frankly, horrifying. I know from my own experience how hard it is to get interviews of any kind from individuals who consider themselves to be the “Grandmasters” of their respective communities. The research that went into this book is just superb.

The history of Tae Kwon Do is fascinating because it illustrates so many of the key themes and theoretical dilemmas that we discuss in the field of martial studies. Its creation showcases the importance of “identity” in a modern setting, and the critical role that the martial arts have played in cementing and legitimizing identity in East Asia. Gillis demonstrates in detail how General Choi Hong Hi basically borrowed and modified Japanese Karate in the 1950s, consciously promoting lies about the origin and history of his art, in an effort to legitimize and strengthen Korean nationalism after years of Japanese domination.

The role of the state in regulating and promoting this sort of discourse is also explored. Both the South and North Korean governments sought to seize control of Tae Kwon Do and use it to further their own political aims. In some cases it was seen as a tool of international public diplomacy, in others it became an ideology that could indoctrinate citizens. Finally, in the hands of ruthless dictators it became a powerful weapon of discipline that could be turned against the disloyal or merely marginal.

The Japanese and Chinese governments have both had numerous interactions with the martial arts organizations and traditions of their own states over the years, and many of the same basic patterns can be seen there. However, in both of these cases the government’s attention was diluted across a number of traditional arts and was shorter lived. I have not come across anything quite like the Korean government’s singular obsession with Tae Kwon Do. Nor has this level of official guidance and “oversight” always been good for the sport.

In many ways the story that Alex Gillis tells is a profoundly sad one. The architects of traditional Tae Kwon Do were unable to hold onto the art that they organized (I hesitate to say “created”) and were forced to watch as a despotic dictatorship used their movement to oppress dissidents (both in Korea and the west) while at the same time transforming different aspects of the style into a toothless competitive sport, controlled through systematic corruption and cheating.

Nor does his book showcase too many individuals who could be characterized as actually living up to the lofty ideals of the art. General Choi Hong Hi is the closest thing that the narrative has to a protagonist. While it is clear that he loved his art and sacrificed immensely for it, it is also undeniable that he was a paranoid, corrupt, and often inept leader who entered into a possibly traitorous relationship with the North Korean government. When figures like Choi are the “friends” of Tae Kwon Do, it is not clear that the art needs many enemies.

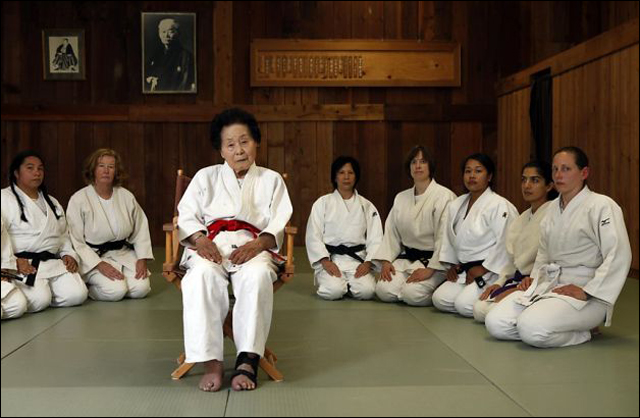

General Choi Hong Hi, creator and long time leader of the International Tae Kwon Do Federation (ITF).

A Killing Art in the Broader Context of Martial Studies

My first exposure to the martial arts happened in a small ITF Tae Kwon Do school in upstate NY. I didn’t stick with the style and my interests moved on to first the Japanese, and then the Chinese arts, where I seem to have found my home. Nevertheless, I have very fond memories of those initial years of practice and study. As a middle school student I never knew or cared about the controversies that surrounded that art. What I did get was a solid foundation in the martial arts that would serve me well as I engaged in my own journey of exploration.

Now, having read Gillis’ account, I am left with a set of profoundly ambivalent feelings. To be totally honest, I suspect that if I still practiced the Tae Kwon Do I would quit. At the same time I am really awed by the many good instructors who were exposed to the sorts of abuses and corruption that Gillis outlines, yet believed deeply enough in their art to find a way to continue to practice and pass it on.

I think that this is where the profound narrative power of A Killing Art comes from. The author understands as much of the history and true nature of Tae Kwon Do as anyone alive. He is intimately familiar with the shortcomings and past failures of his chosen style, but he stands by it anyway.

While he set out to write a historical account, I think that this book has evolved into something more. I see it as an open letter to the Tae Kwon Do community (and in particular its leadership) reminding them of where they actually came from and extolling them to do better. To live up to their promises of reform, to no longer betray the trust of all of the students who have studied and competed in its ranks over the years.

Undergraduate students will appreciate the unflinching honesty of this account and the direct nature of the writing. Parts of the book read like a spy thriller, other sections like a corruption investigation. As a reporter Gillis doesn’t impose any sort of theoretical apparatus on his account, nor does he seek to situate his study within the larger literature on the martial arts. I think that this decision is basically a good one. It allows his book to be introduced or framed in a number of different ways depending on what sorts of classroom discussion you wish to have. It will also serve as a great database for research papers.

I strongly recommend A Killing Art for anyone interested in learning more about history of the Korean martial arts. The book is well written and extremely well researched. Even though Gillis is not writing for an academic audience he has done the field of martial studies a great favor. We desperately need more accounts like this. Hopefully other authors will sit up and take notice.

Be sure to check out our interview with Alex Gillis where he discusses the process of writing A Killing Art and its reception by the martial arts community.